CHANGELOG

Educational systems around the world are increasingly based on curriculum standards. These standards are intended to be used as the blueprint for all components of the educational system: - Standards define what should be taught (content standards). what skill students should develop (competency standards), and the level of proficiency students must attain (proficiency standards) - Content producers use these standards to create textbooks “aligned” to the standards - Educational institutions use the standards to plan their programs - Teachers use the standards to build the curriculum for their classes - Examination are created to test the specific knowledge/skills defined in the standards

Curriculum standards usually describe what learners should know at different grades in a given subject and specific competencies they must demonstrate. Curriculum standards are made of individual statements with well-defined expectations, and are usually organized in hierarchical structures like:

Subject

> Grade

> Topic

> Subtopic

> BenchmarkEach level of this hierarchy defines specific descriptions of the content, learning objectives, and competencies that are expected of students.

The structure and content of curriculum standards varies widely. Each standard entries can have any subset of the following attributes:

2.MD.D.10The wide variability of the structure and information contained in each standard poses a difficult challenge when trying to create computer representations of them.

The folder CurriculumDocs contains examples of complete curriculum standards documents form several countries.

In the next section we’ll present excerpts of individual statements from each of these documents.

In order to understand great variability of information associated with standards statements, we’ll now look at representative excerpts of individual statements from different countries.

Australia is an excellent example of what is possible when curriculum standards are available.

Notes: - The Australia digital learning resources metadata efforts (MEX, SHEX) assumed a “closed system” model where all content is produced within Australia and tagged appropriately. Their current projects will rely on “open system” with publishers independently producing materials, but curriculum correlation tags will continue to play a role.

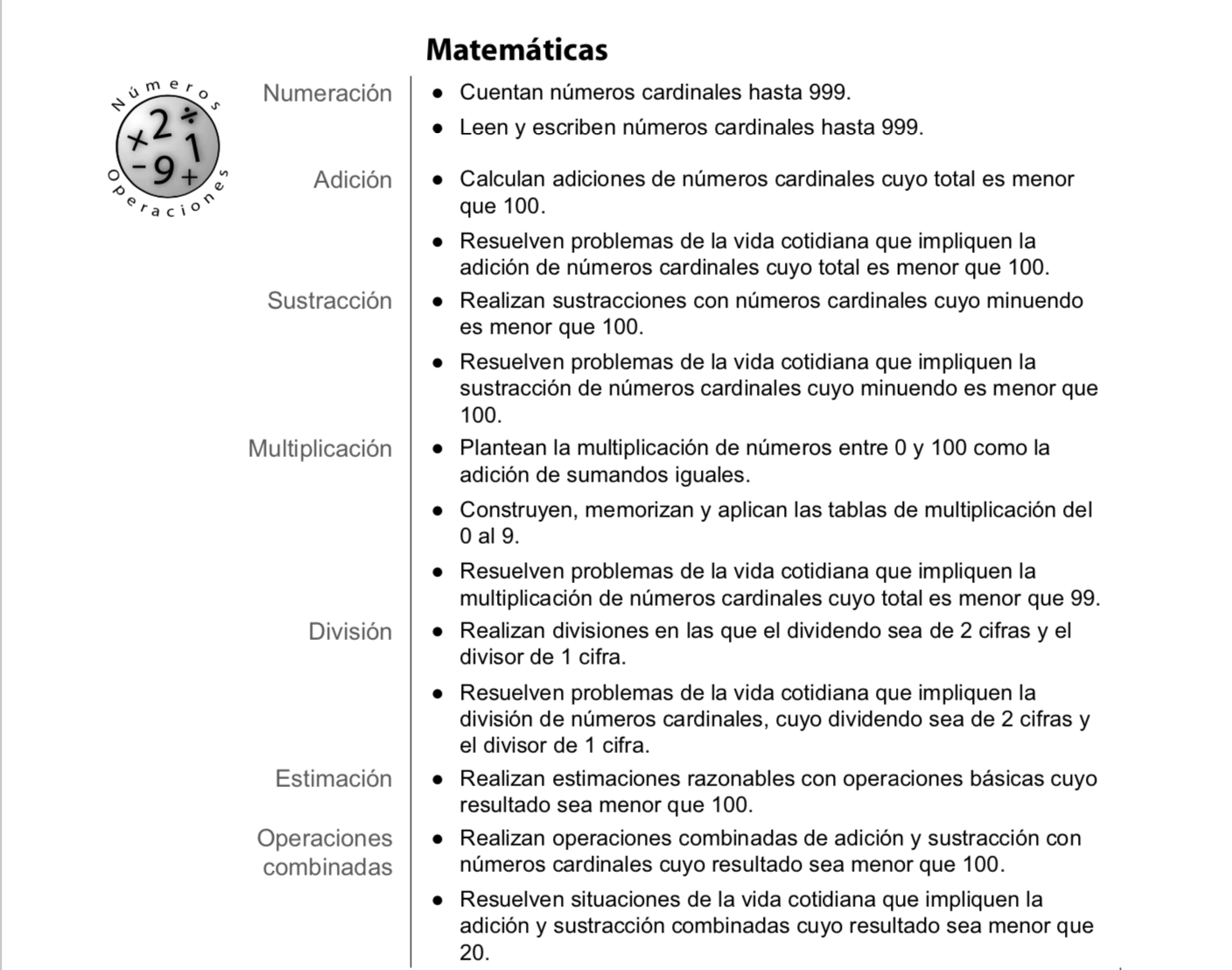

The Honduras educational standards (Estándares Educativos Nacionales) are an interesting case because they are available in two alternative organizations: by grade level and by topic.

Curriculum standards for Grade 2 Math, in the block “Números y Operaciones”:

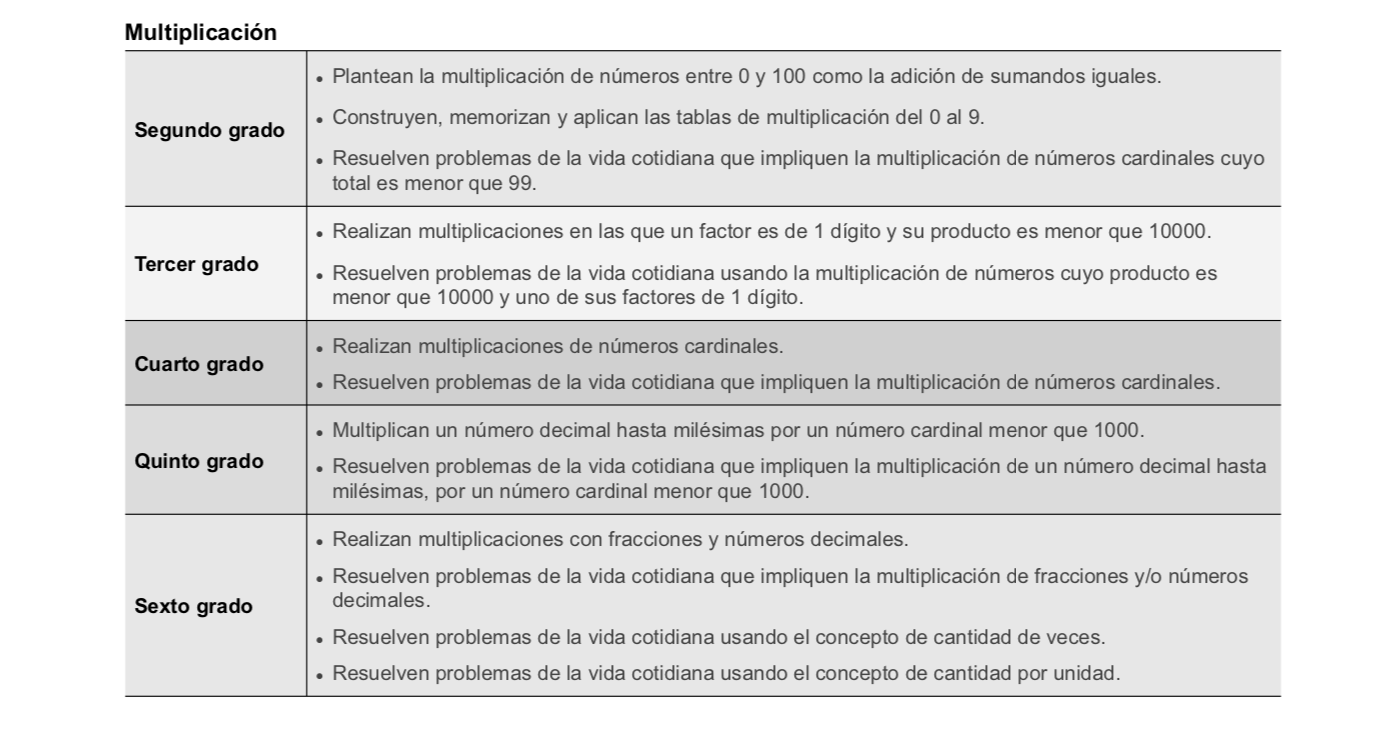

The same statements also appear appear in the “Multiplicación” component progression across levels:

Notes: - The Honduras standards do no have unique identifiers associated with each statement, so we would need to invent them. For example, the three statements in “Matemáticas > Segundo grado > Números y Operacione > Multiplicación” could be tagged with Mate.2.NO.M.1, Mate.2.NO.M.2, Mate.2.NO.M.3. - The Honduras curriculum standards are a good example of a single-hierarchy structure: the subjects, blocks, components, and statements can be represented as a tree.

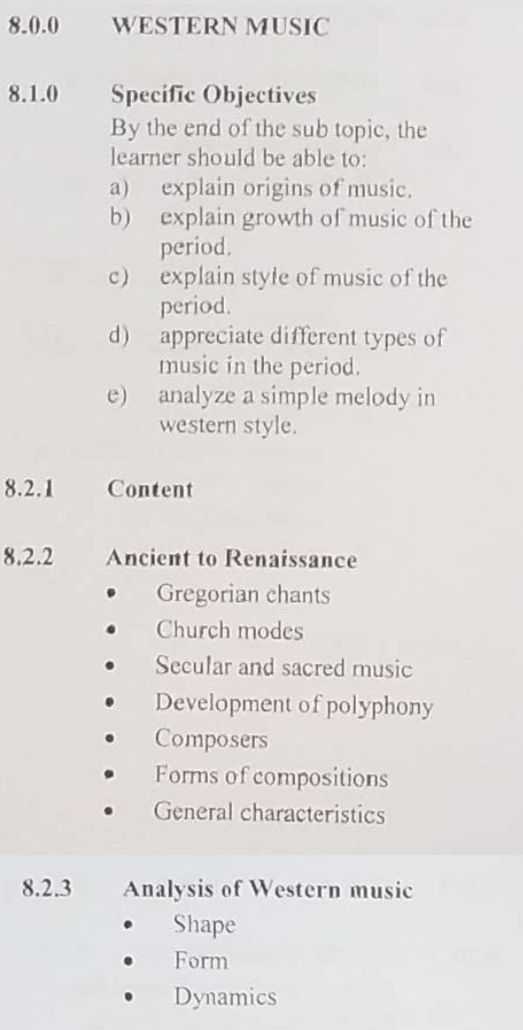

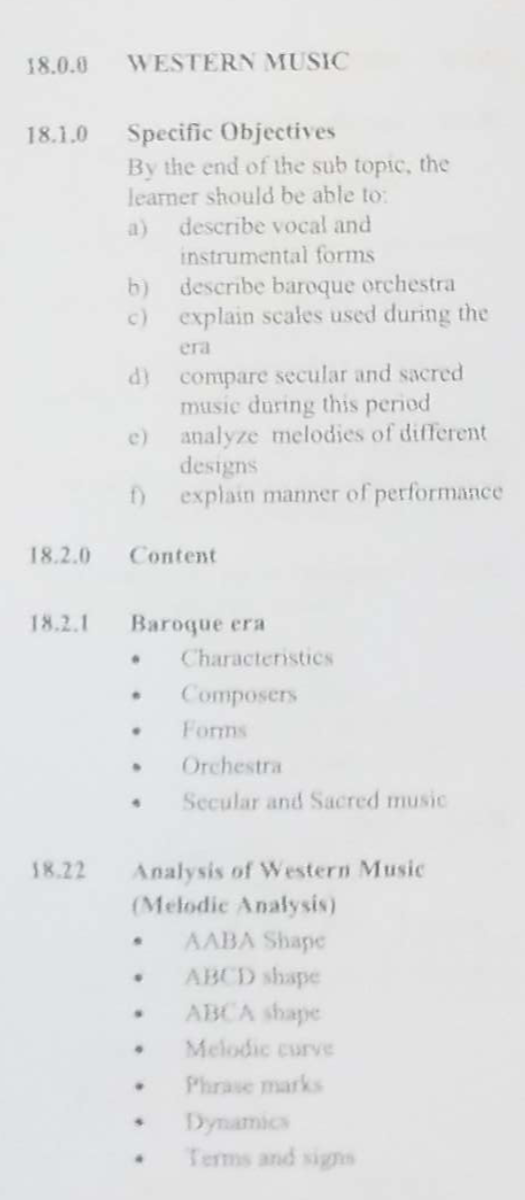

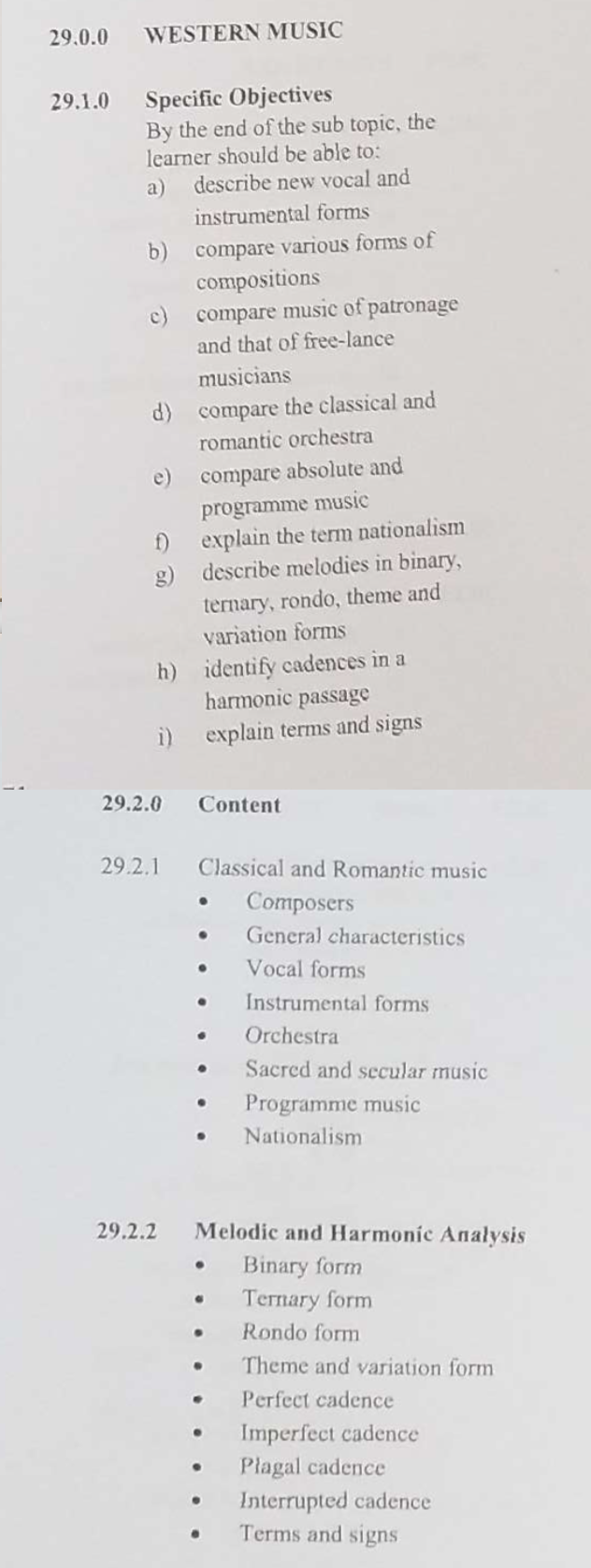

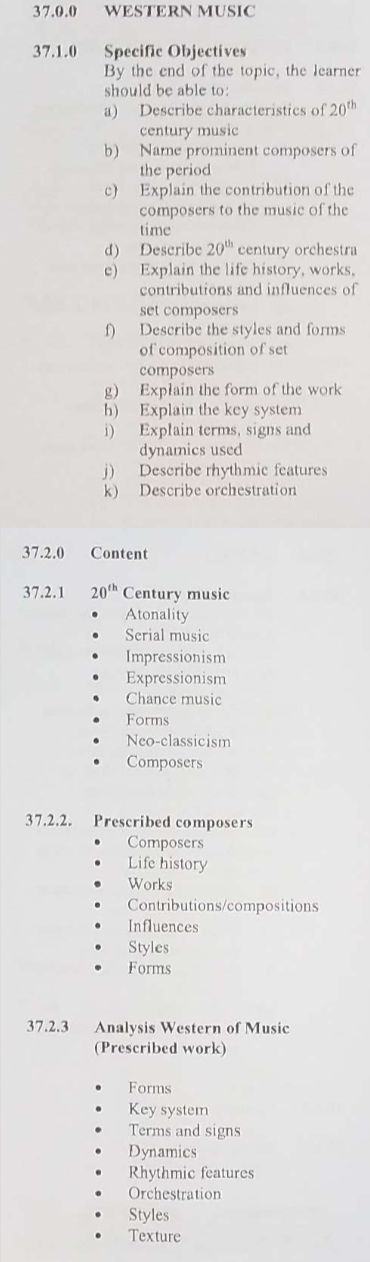

The KICD curriculum standards for Music are a good example a topic that appears repeatedly in several grade leves. The topic “Western music” appears in Form One, Form Two, Form Three, and Form Four with progressively more details:

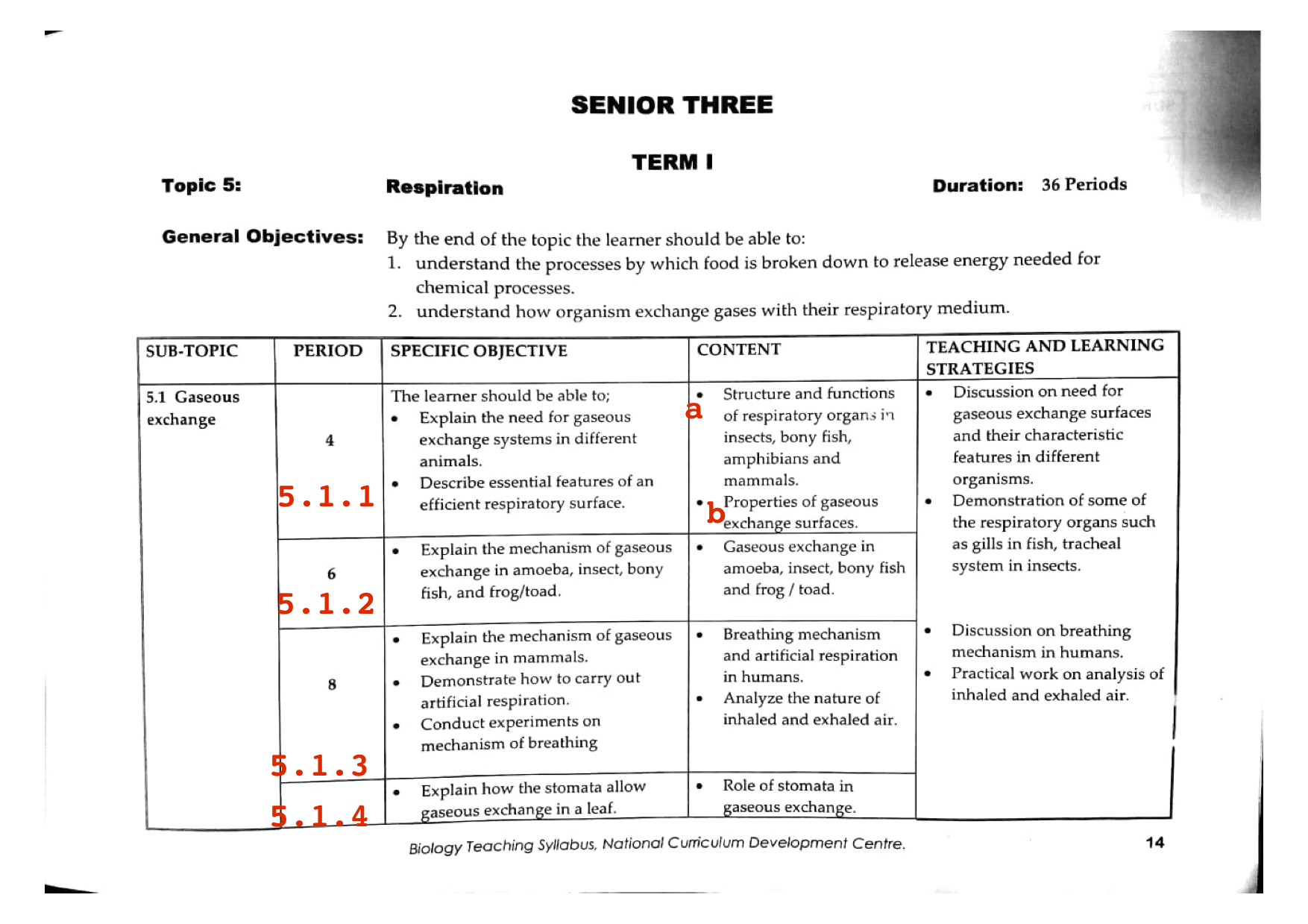

This is an example of a curriculum standard presented in table format, with different components presented in the columns of the table.

The figure below shows the first part of the topic “Biology > Senior Three > Term I > Topic 5”:  See here for part two and part three of the statement.

See here for part two and part three of the statement.

Notes: - This topic contains two subtopics “5.1 Gaseous exchanges” and “5.2 Tissue respiration” - This sections within each sub-topic do not have titles—they simply correspond to different groups of specific objectives and content. We have assigned identifiers (numbers shown in red) to represent these sections. - This standard statement has been manually transcribed to digital form, see here

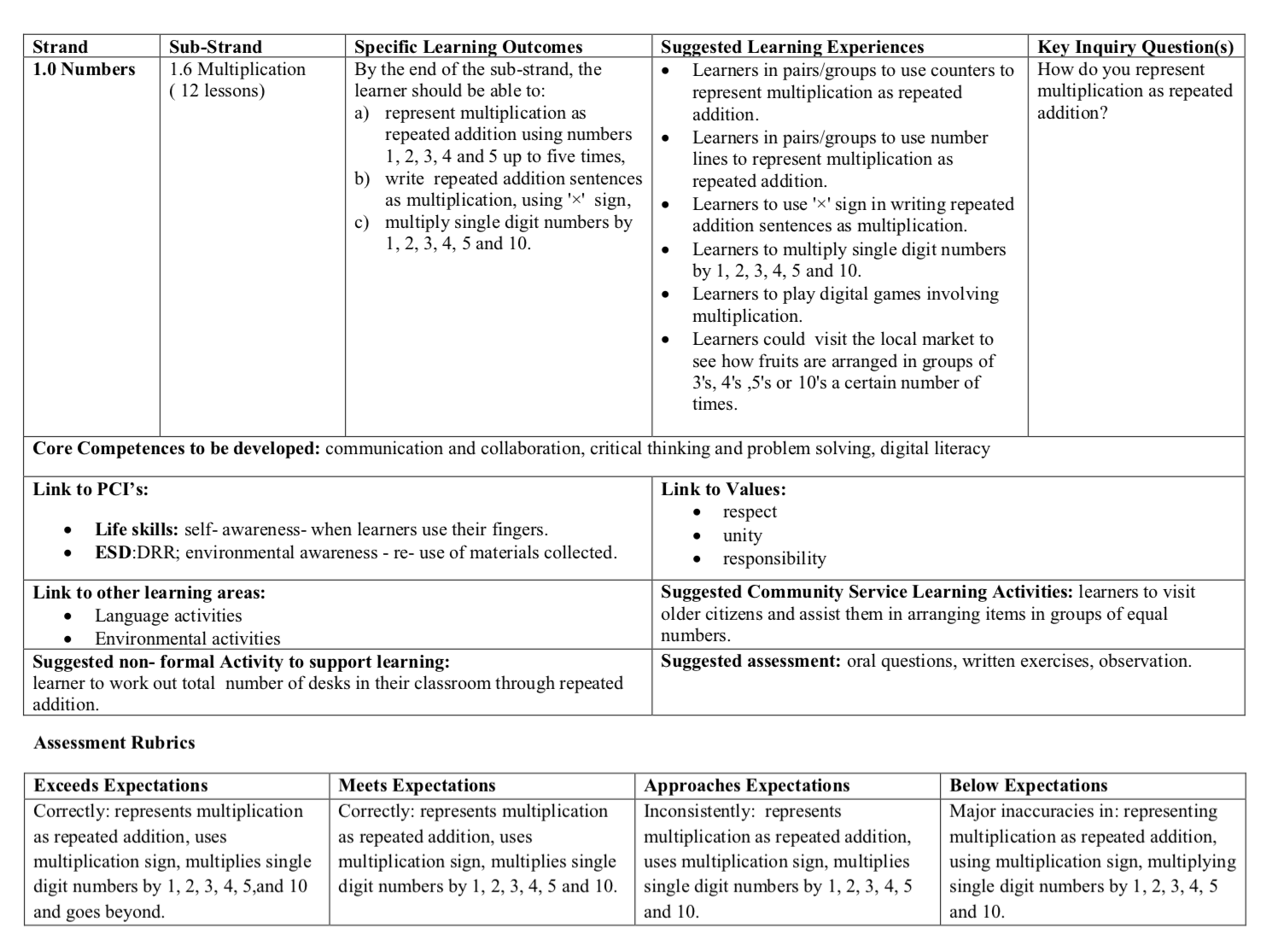

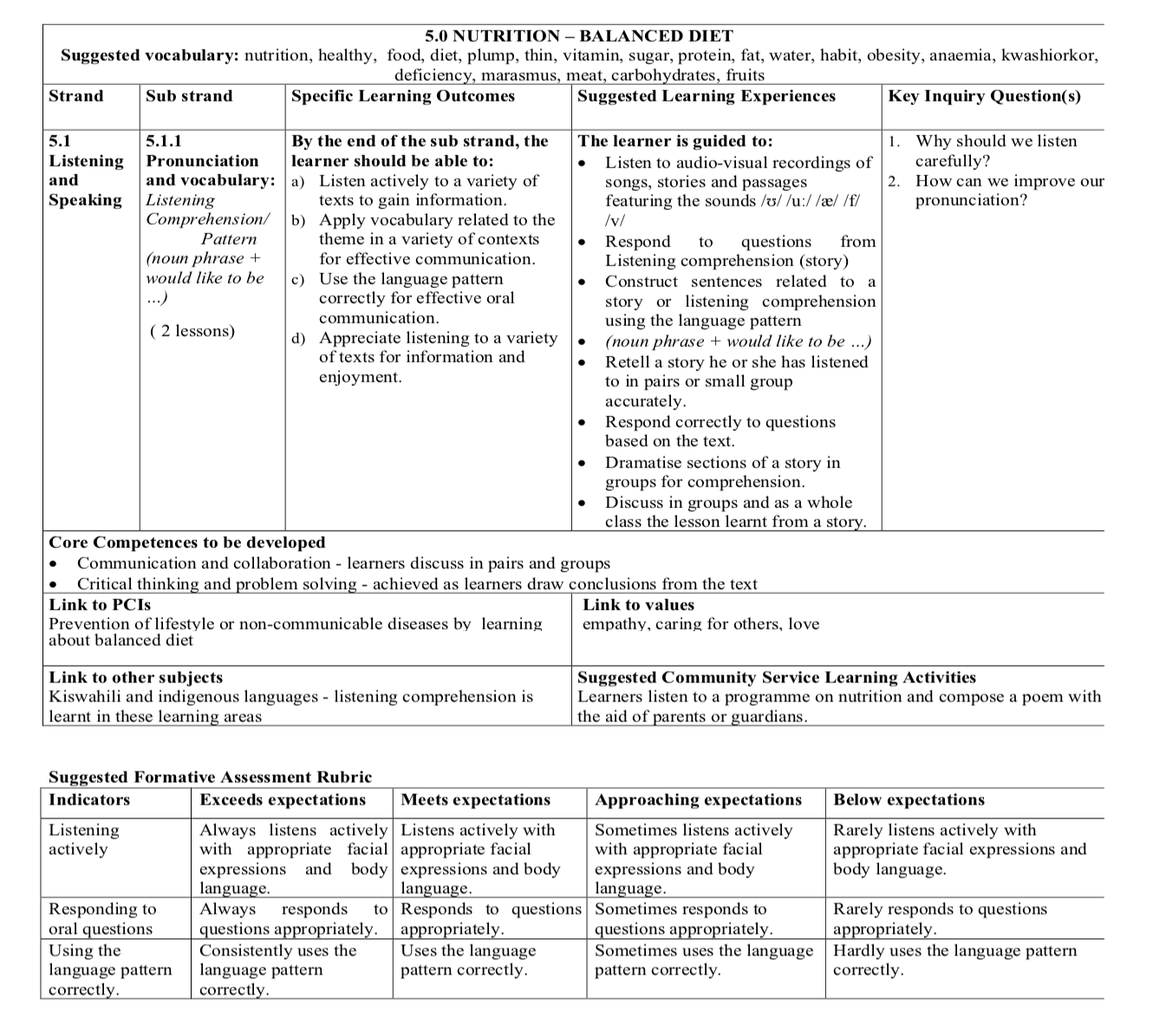

The new Kenya CBC (competency based curriculum) standards are very detailed and include numerous components, dimensions, and cross cutting concerns, all presented in tables.

Example for the math sub-strand: Mathematics > Grade 2 > 1 Numbers > 1.6 Multiplication:

Another example for the English sub-strand English > Grade 4 > 5 Nutrition > 5.1 Listening and Speaking > 5.1.1 Pronunciation and vocabulary:

Notes: - Note the number of different elements specified in the standard (time allocation, specific learning outcomes, suggested learning experiences, key questions, core competencies, learning areas links, etc.) - Creating a faithful and complete digital representation of all the information in this table will be a significant challenge: we would either need a very flexible/extensible data model or have to represent only part of the information.

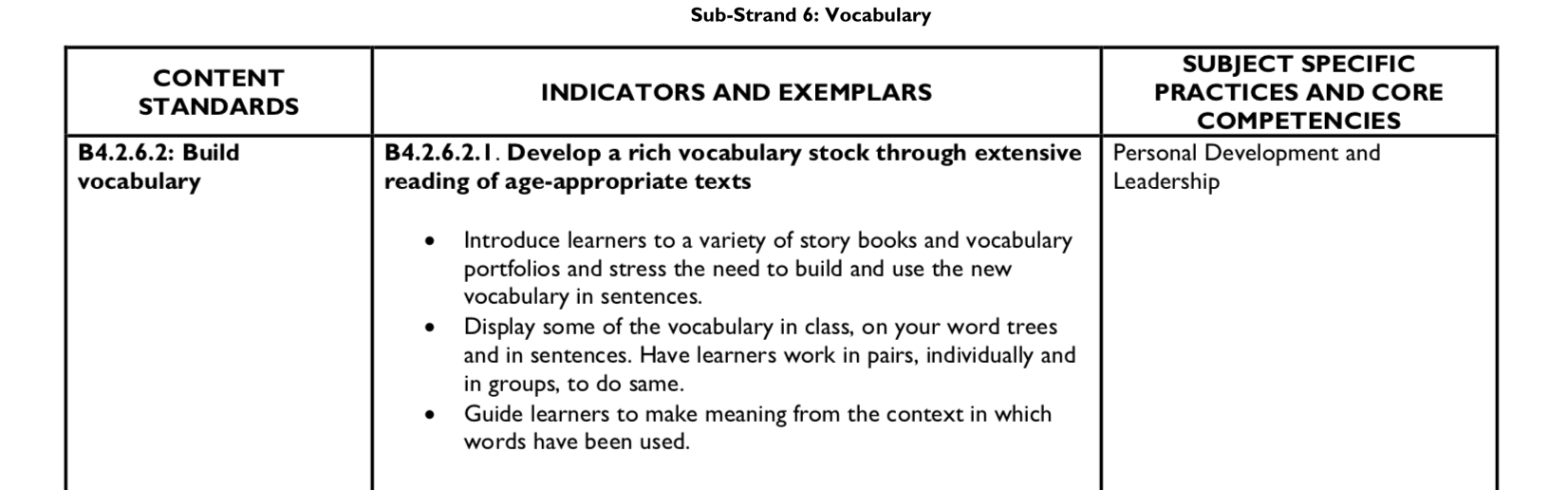

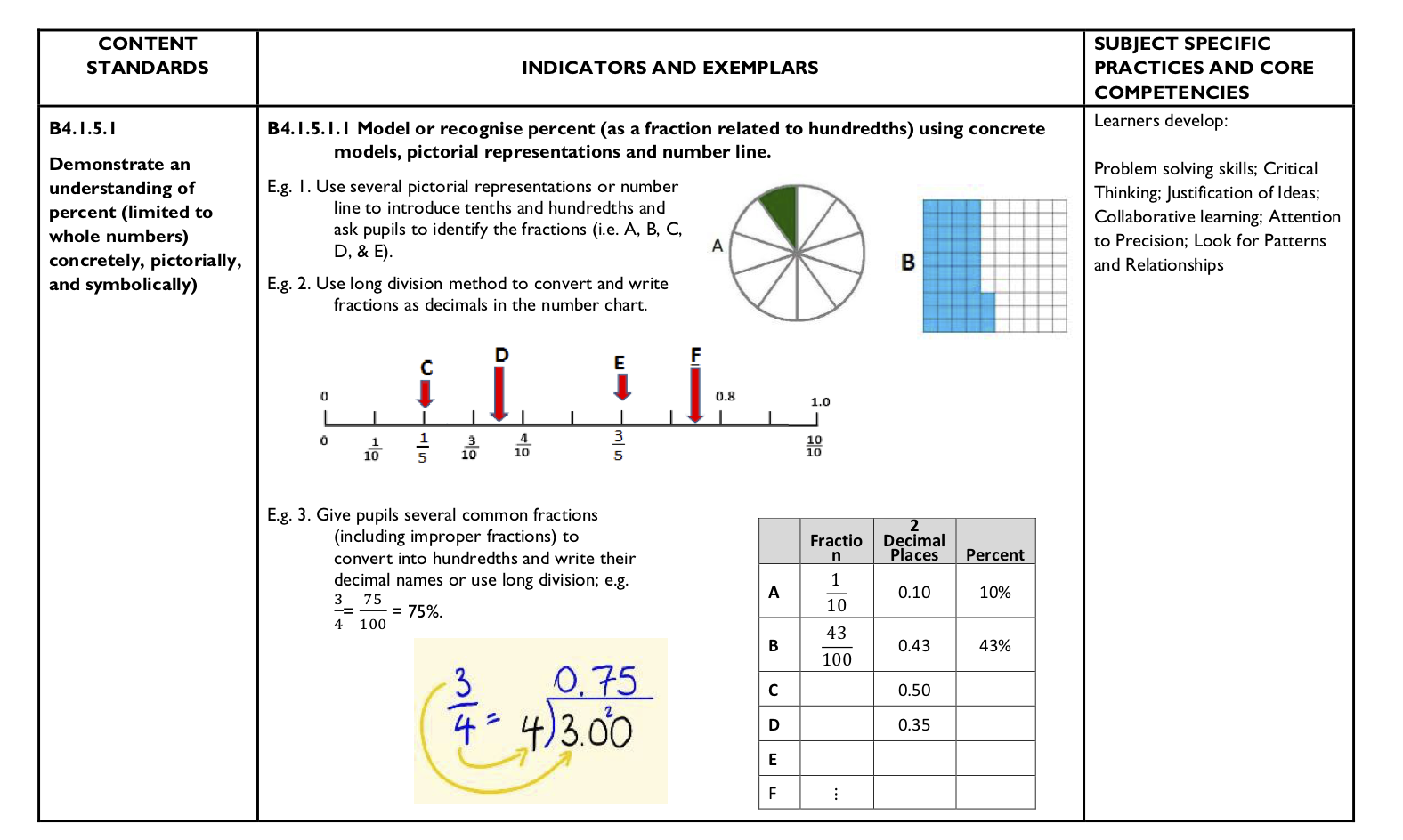

The Ghanian curriculum standards are available as PDFs from the NaCCA website. Each statements in the Ghanian curriculum standards has an identifier of the form Bx.y.z.v.w, where x is the grade level, y is the strand number, z is the sub-strand number, v is standard number, and w is learning indicator number. The same structure is used in all subjects, so we’ll only show two representative examples.

English example B4.2.6.2:

Math example B4.1.5.1:

The folder CurriculumSamples/06_Ghana contains additional examples.

Notes: - The Ghanian curriculum standards contain a lot of useful examples, which would be important to capture as part of the digitization process. - The examples contain math equations, images, and illustrations.

We’ll now summarize some prior work done towards building data models for curriculum standards, which has been an active area of research for the past 20 years.

There are three notable prior efforts to produce a schema for digital curriculum documents:

We’ll provide detailed notes for each standard and related research below.

The Achievement Standards Network (ASN) the most substantial effort to date to define a data model for curriculum documents. Achievement Standards Network Development of the ASN-DF dates back to 2000 and gained significant momentum with near decade-long funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) starting in 2002 to the Information School at the University of Washington and its collaborator, JES & Co., a U.S. non-profit.

The ASN uses an entity-relationship model with two entities - Standard Document and Statement. These entities are each assigned an inherently globally unique Uniform Resource Identifier (URI). ASN URI’s are “resolved” over the web via the ASN Resolution Service. The most basic resolution is the HTML view that you see when you visit any ASN URI in your web browser but the real interoperable magic happens when you request a RDF serialization for a particular ASN URI. – source: ASN overview

The goals of the NSF funding were two-fold:

The ASN repository contains hundreds of curriculum documents from USA, Australia, and Canada. In addition to the attributes and relationships defined for the objects in this domain, each of the above standards defines a set of controlled vocabularies for specifying jurisdictions, subjects, education levels, publication status, and other attributes.

The two papers (Stuart A Sutton 2008) and (Stuart Allen Sutton and Golder 2008) provide a good summary for the research and design that went into designing the ASN:

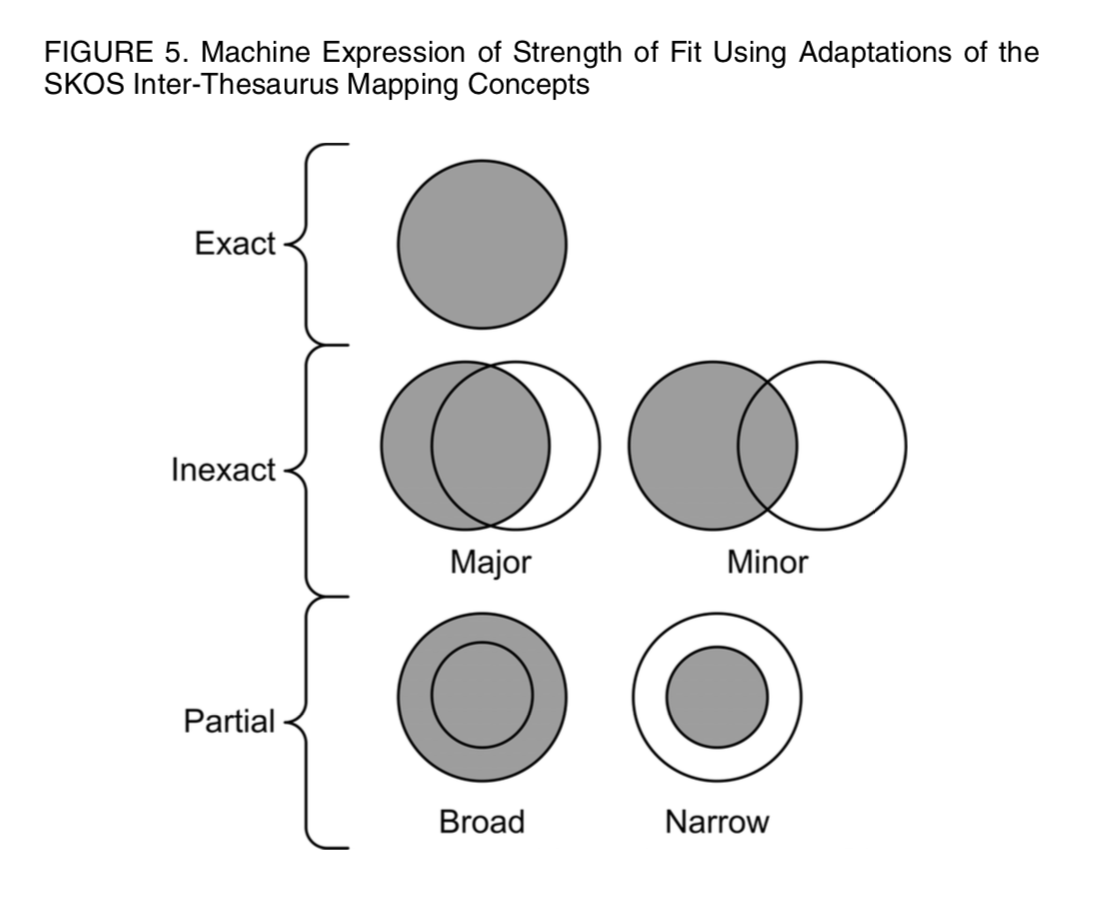

The ASN framework specifies the following types of relations that can exist between two standard statements: broadAlignment, exactAlignment, majorAlignment, minorAlignment, narrowAlignment.

Similar to the above, the ASN framework specifies the following types of relations that can exist between a learning resource and a standard node: exactCorrelation, narrowCorrelation, broadCorrelation, minorCorrelation, majorCorrelation, etc.

The terminology broad/narrow is inspired from the SKOS concepts of broadMatch and narrowMatch.

For more information, see the Research/ASN/ folder on github.

The Credential Transparency Description Language (CTDL-ASN) schema is based on the ASN, but uses the terminology of “competencies” and “frameworks” instead of “statements” and “documents.” This schema is developed by Credential Engine and used by employers, accreditation agencies, and educational institutions to edit, publish, and find work-related competencies.

The CTDL-ASN schema has an active ecosystem of tools and services around it:

For more information see the Credential Engine Technical Site, the CTDL Handbook, and the Research/CTDL-ASN/ folder on github.

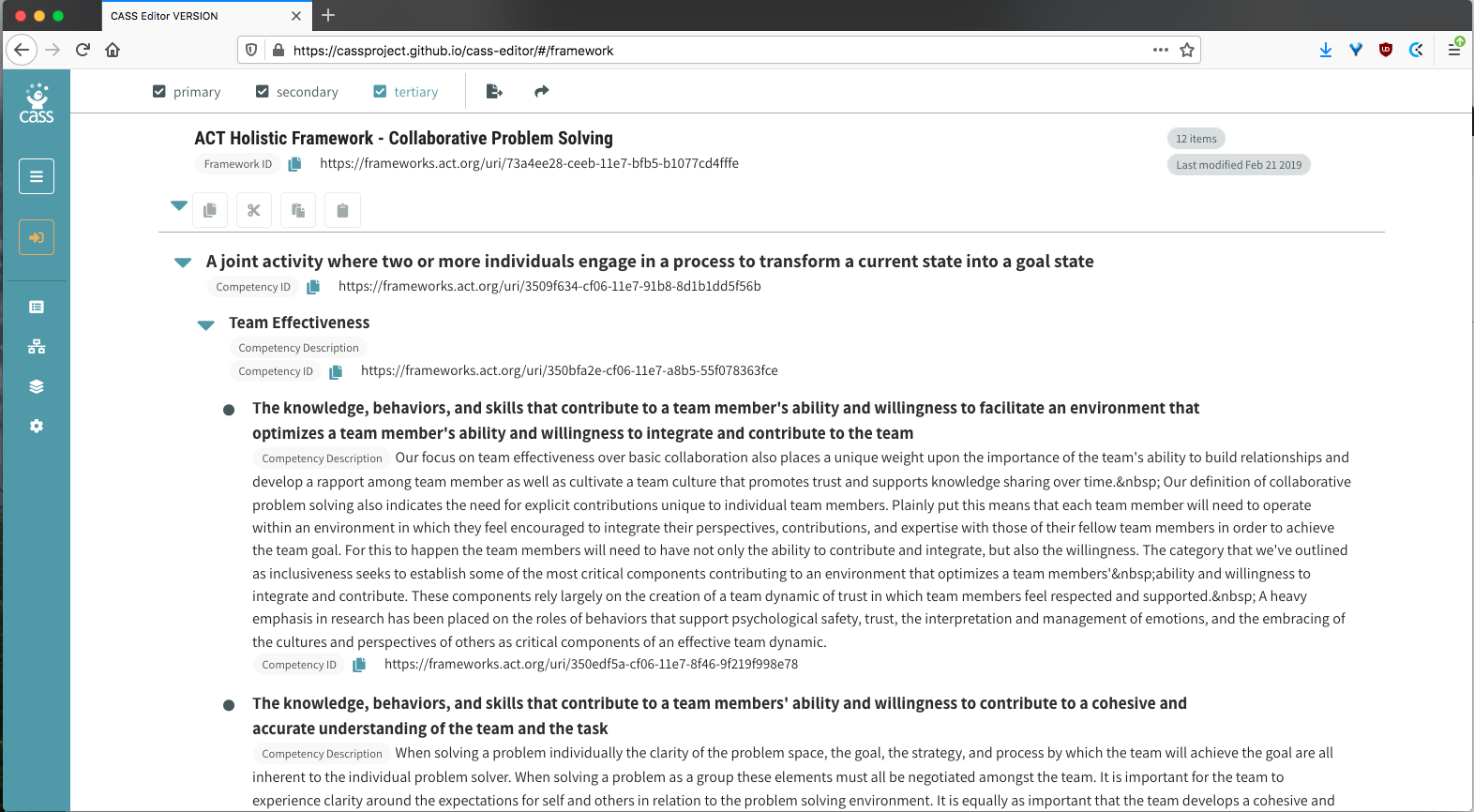

The CaSS editor is an web application for importing, creating, editing, and exporting competency frameworks developed by EduWorks. The CaSS editor is open source and used as the new Credential Engine competency manager.

The CaSS supports importing competency frameworks from CASE schema, and a number of other structured formats as CSV, JSON-LD, etc.

The screenshot below shows the browsing interface for frameworks, which you can see for yourself here.

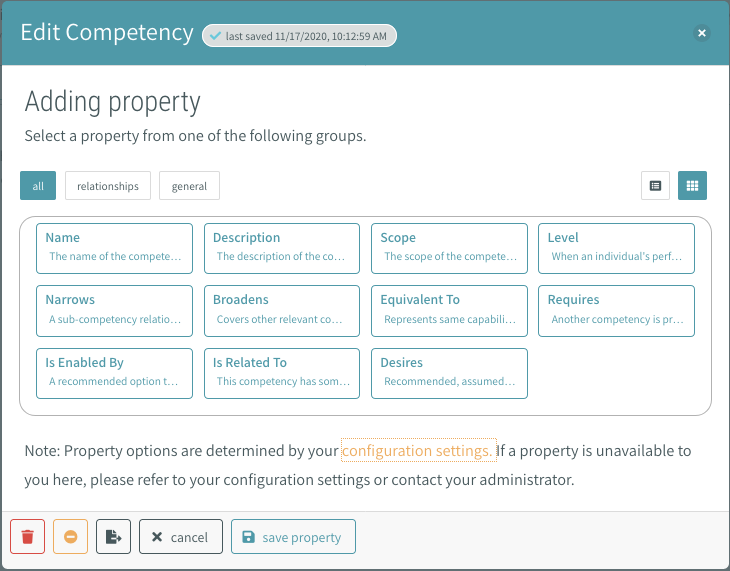

The browsing interface allows three levels of metadata details: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Each competency can be associated with one of the properties within the CaSS schema:

The set of available and required properties in the CaSS editor is controlled by a configuraiton.

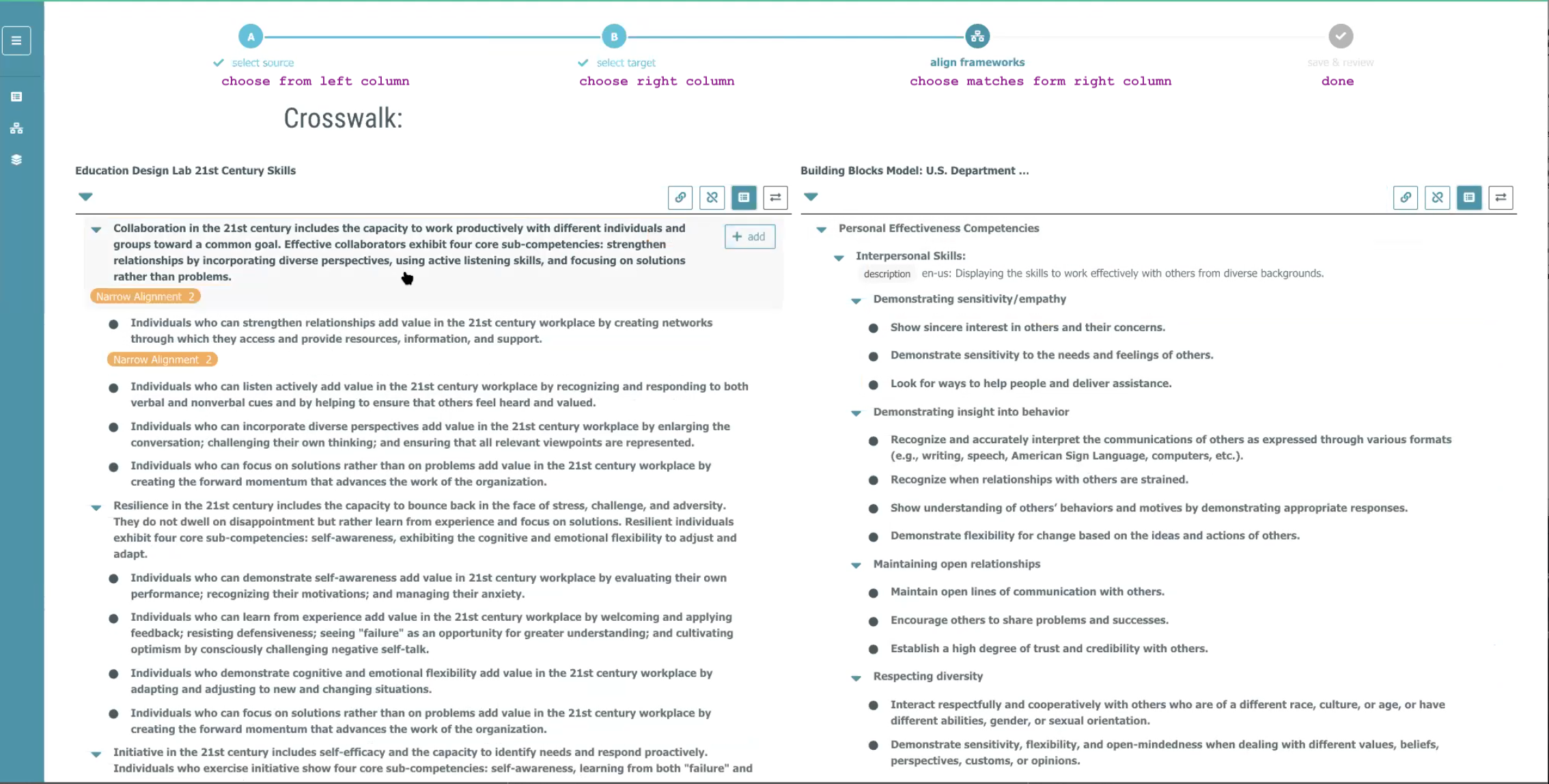

The CaSS editor can be used to create crosswalks between frameworks through two-column interface:

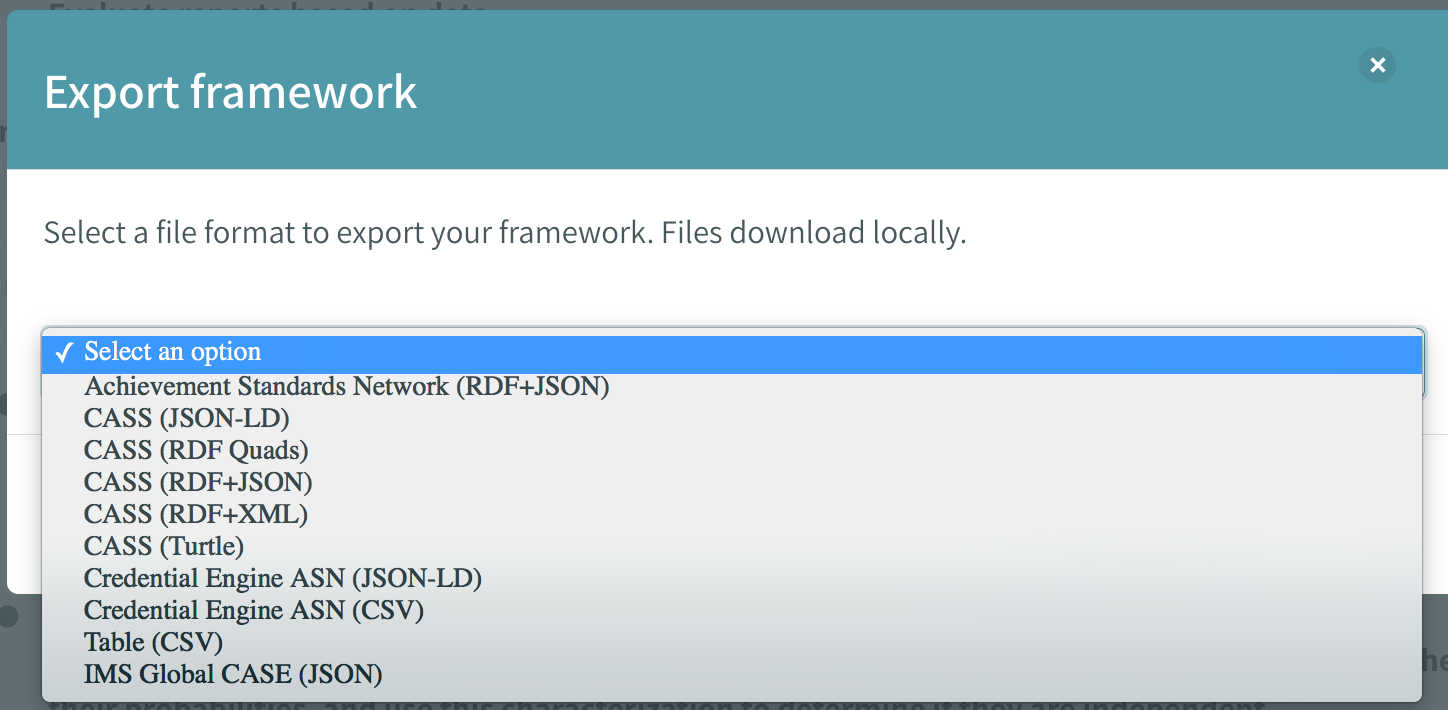

Frameworks can be exported as ASN (RDF), CTDL-ASN (JSON), CSV, and CASE formats:

This standard defines a set of data models for competency frameworks, competency documents, entries, associations, and rubrics and also codifies the network protocol for exchange of these standards. The standard defines a controlled vocabulary for the different association types between standard entries.

CASE adoption mainly by US states: Texas, Georgia, LearningMate(South Carolina), and Florida.

Competencies & Academic Standards Exchange (CASE) http://www.imsglobal.org/activity/case

Presentation and demo videos from YouTube (talks about the need for digital standards provided by authoritative source + matching standards between different vendors and jurisdictions)

For more information, see the Research/ASN/ folder on github.

OpenSALT is a reference implementation of CASE.

There are several other projects related to defining work-related competencies that are currently being developed:

The frameworks presented above are designed for work-related competencies, but the used cases for the data models being developed are similar to the use cases for curriculum standards—in both cases the goal is to establish shared identifiers that allows for interoperability between different systems.

There are several standards for specifying metadata of “learning objects” which are interesting to look at in order to understand existing methods for attaching standards alignment information to content items. Alignment to standards is generally done by “tagging” content items with curriculum standard identifies (short codes or URIs).

This is a standard for all metadata associated with a learning resource, including lifecycle, technical, educational, and copyright domains. The LOM standard is known as IEEE 1484.12 and as also as IMS Learning Resource Meta-data (LRM) Version 1.3. The LOM standard serves as the basis for several other standards and packaging formats.

The classification category in the LOM standard can represent associations between learning objects and curriculum standards through the use of purpose and taxon path fields. For example, setting purpose to “educational level” can be used to indicate broad grade-level alignment, while purpose values educational objective, competency, and skill level can be used to indicate more specific correlations. In each case the corresponding taxon path would be set to the point to the appropriate. The standard does not specify any required format for the taxon.

For more information, see the Research/LON/ folder on github.

The Learning Resource Metadata Initiative (LRMI) specification is a collection of classes and markup properties designed for describing educational resources. The specification is designed to be used in conjunction with the Dublin Core metadata terms.

See LRMI Metadata Terms for details of the specification.

The following code snippet shows an example metadata record for a lesson plan that makes use of the LRMI fields to specify the educational audience (teachers), what the resource is about (by reference to a WIKIDATA identifier), and specifies the education level with respect to Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF).

{

"@context": "https://schema.org/",

"@type": ["WebPage", "LearningResource"],

"url" : "http://example.org/lessonplan",

"name": "Lesson: The Declaration of Arbroath",

"about": {

"@id": "https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q598496"

},

"learningResourceType": "lesson plan",

"audience": {

"@type": "EducationalAudience",

"educationalRole": "teacher",

},

"typicalAgeRange": "10-12",

"educationalLevel": {

"@type": "DefinedTerm",

"name": "Level 2",

"inDefinedTermSet": {

"@type": "DefinedTermSet",

"name": "SCQF",

"url": "https://scqf.org.uk/"

}

}

}The LRMI defines the educationalAlignment property which for linking resources to curriculum standards. Each standard alignment correlation can be qualified by specifying an alignmentType property, which has recommended (but not restricted) values: assesses, teaches, educationLevel, etc.

For more information, see the Research/LMRI and DCMI/ folder on github.

The main purpose of digitizing curriculum documents is to allow educational content to be explicitly “tagged” with the curriculum standards identifiers. The links between content and curriculum standards are called “content correlations” in the literature.

For more information, see the papers in the Research/ContentCorrelations/ folder on github.

Assuming the existence of curriculum documents in digital form from multiple jurisdictions, the next logical step is to try to find equivalent entries in different curriculum standards. This standard-to-standard mapping is also known as a curriculum crosswalk.

Obtaining a crosswalk between two curriculum standards would allow content produced for the curriculum of one country to be used to another.

During October 2019, a hackathon co-organized by UNHCR, Learning Equality, Google.org, Vodafone Foundation, and UNESCO was held with the goal of developing tools for digitization of curriculum documents and semi-automated discovery of crosswalks between standards. You can read the results of the report below:

For more information, see the papers in Research/StandardsAlignment/ folder on github.

The problem with curriculum standards is that they are not universal. Far from it! Different counties, states, school boards, and even schools use different standards.

The previous section touched upon some of the approach of finding standard-to-standards alignments, and content-to-standard correlations. This section we’ll discuss a different approach, which is to define common, “universal” standards that can facilitate finding standard alignments and content correlations.

The McREL Compendium of Academic Standards was developed by combining the information from multiple curriculum standards of the time (’90s ) and organizing all the knowledge statements in a consistent manner. Read additional details about the process.

The amount of work that must have gone into producing this compendium is staggering. Unfortunately, many of the standards included in the compendium are now deprecated so the McREL Compendium needs to be updated to continue to be useful.

In (Kendall 2003), the author describes the “Problem of Varying Grain Size” that occurs when trying to establish a content correlation or alignment between standards when the descriptions use a different granularity. In this case, no clearcut alignment statement can be made since only part of one standard matches the other. Such partial matches limit the usefulness of all downstream information retrieval tasks.

The author proposes a solution which is to build modular standard statements that consist of a general benchmark statement which are composed of multiple independent vocabulary terms and knowledge statements. Curriculum experts who are aligning content or standards to can then choose which a specific subset of these vocabulary terms and knowledge statements when defining relations.

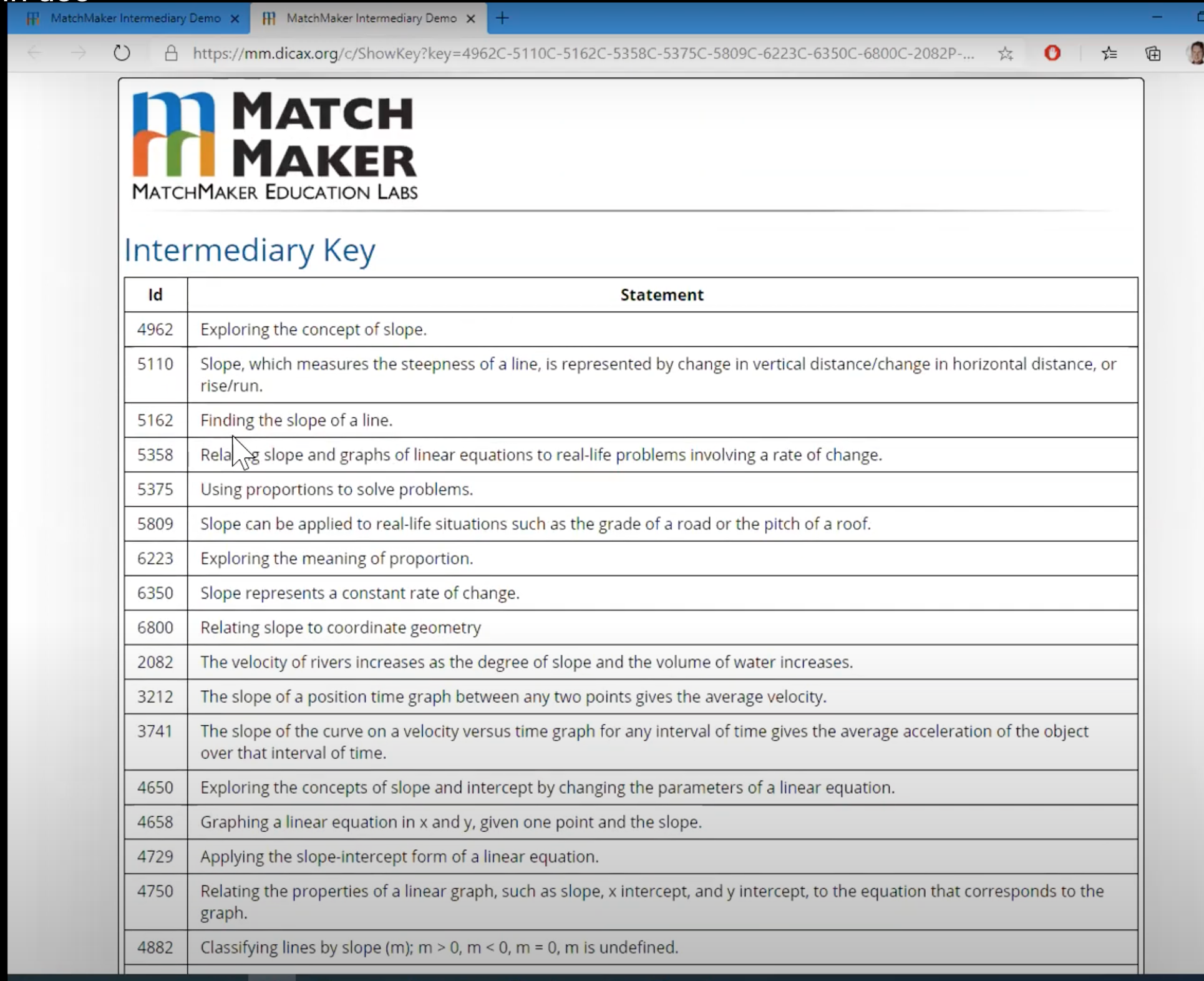

A similar ideas can be seen during the MatchMaker demo presented at the “LRMI Metadata in use” online conference, where a math standard from the CCSSM is linked to a “Intermediate Key” consisting of very granular concepts:

This in turn allows the user to find similar standard entry in another state, something that would have been difficult to do directly, without passing through the “Intermediate Key” representation.

This is a approach is very powerful, but compiling these the list of intermediate keys will be a tremendous effort requiring lots of domain expertise.

There is an interesting recent effort by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics to come up with “global” curriculum standards for reading and mathematics:

The GPF articulates the minimum knowledge and skills that learners should be able to attain along their learning progressions at each of the targeted grade levels in the two subject areas. The purpose of the GPF is to provide detailed minimum proficiency expectations (called Global Proficiency Descriptors—GPDs) that countries, along with regional and international assessment organizations, can use as a foundation for linking existing – and future – reading and mathematics assessments via benchmarks. This will provide the framework for comparing results from different assessments, both within and across countries, and for reporting on SDG 4.1.1.

Essentially, if UN wants to measure SDG 4.1.1 progress and compare countries, they need to define a “global” curriculum standard. For reference, Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4.1.1 (a) and (b) measure:

Proportion of children and young people: (a) in grades 2/3 and (b) at the end of primary achieving at least a minimum proficiency level in (i) reading and (ii) mathematics

This is interesting for two reasons:

The survey of existing schemas for learning resources and curriculum standards and the associate research paints a clear picture of the difficulties associated with the task of digitizing curriculum documents. The following general observations can be made:

Overall there is a lot to learn from this prior work and all new standards proposed should support the above metadata aspects and aim to be interoperable with them.

Kendall, John S. 2003. “The Use of Metadata for the Identification and Retrieval of Resources for K–12 Education.” In International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, 109–17.

Sutton, Stuart A. 2008. “Metadata Quality, Utility and the Semantic Web: The Case of Learning Resources and Achievement Standards.” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 46 (1): 81–107.

Sutton, Stuart Allen, and Diny Golder. 2008. “Achievement Standards Network (Asn): An Application Profile for Mapping K-12 Educational Resources to Achievement Standards.” In International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, 69–79.